Being startup employee number one

This article was originally published on Sifted on May 19th, 2021.

——

In 2011, Triin Hertmann spotted a post on Facebook from one of her former colleagues at Skype, Taavet Hinrikus. He was looking for somebody to help with customer support on a new business he was starting — some kind of currency conversion boutique.

Hertmann, who was at the time on maternity leave with her first baby, said it was not the kind of role she was especially looking for: “The last thing I was thinking about was joining a startup.”

“But then Taavet contacted me, saying we need someone in Estonia to start the office and set up the payment operations. And I said, yeah why not? I can do it while my baby’s sleeping.”

It was, in hindsight, a pretty good decision. Hertmann became Wise’s first employee — and Wise (formerly TransferWise) went on to become a $5bn company.

“It’s been really transformational for me,” says Hertmann, who received stock options when she joined and is now bootstrapping her own fintech startup. “It’s given me financial freedom for life.”

The route to riches

Some early employees, like Hertmann, join startups knowing that it could be a very savvy financial move.

“I saw what options could do for people,” says Hertmann, who had stock options at Skype when eBay bought the company in 2005. “This personal story really helped me hire people [at TransferWise] and show them the potential valuation of these kinds of stock options.”

“When I joined, I cut my salary in two — my base salary had never been so low,” says Anh-Tho Chuong, who joined French fintech Qonto in 2016 when it was just the two founders and an idea. “I saw the potential so I tried to maximise my equity.”

Others don’t. “Nobody even knew what equity was,” says Tony Honkanen, who joined Finnish delivery startup Wolt in 2015 when it had just two other employees. “That came after the Series A with EQT [Ventures]. [Wolt CEO] Miki called us into the office, said we’d done a good job and gave us a piece of paper. He was excited about it.”

“[That piece of paper] had a bit of a different value back then.”

A bonkers decision

Despite that (very slim) chance of making millions, joining a startup as its first employee is not for everyone.

“From one point of view, it’s a bonkers decision,” says Harry Marr, who joined London fintech GoCardless as its first employee in 2011.

“You’re taking a similar level of risk to the founders — it’s very likely to fail, you’re likely to end up out on your ass — and yet you take an order of magnitude less equity. You work as hard in the early days, but you’re not making a load of investor contacts or getting press attention. In that sense, it’s a pretty bad deal.”

“I think it’s the hardest position,” says Chuong, who was VP of growth at Qonto. “Being a founder is hard, but founders have peers and a community. The first employee is not quite a founder, but not quite like the other employees. It’s really tough, it can get very lonely — and often they don’t get enough credit.”

“Some founders can put a lot of pressure on early employees, but they don’t get the same reward. Of course, they get equity and salary and a lot of founders don’t — but it’s still a lot of mental load.”

Rock, paper, scissors

Risk, stress and loneliness aside, it can also be pretty fun to build something (sometimes quite literally) from scratch.

“We’d do rock, paper, scissors to decide who would do deliveries, who’d do dispatch and who’d do customer service,” says Honkanen. “In the first month, we were doing customer operations in the car while doing deliveries. It was quite hectic.”

“We’d get a ping in Slack every time a customer made an order,” he adds. “We’d copy and paste the restaurant address and the customer address and then assign to a driver from a map… all by hand.”

The early days at UK meal kit company Gousto were somewhat similar. “On Tuesdays, we would do customer delivery and clear away all of the laptops and turn the office into a fulfilment centre,” says Aidan Willcocks, who joined as an intern in 2012 after seeing the role advertised on jobs board Workinstartups.

He’s now chief of staff — but has also been marketing manager, head of performance and unofficial handyman. “At some point, I volunteered to do handy work around the office like putting up a TV — and then I always got lumped with the DIY projects.”

Learning on the job

First employees often, like founders, find themselves doing jobs that they’ve never done before. That can be a blessing, and a curse.

“I’ve been lucky; I’ve rotated across a lot of functions — marketing, HR, product, ops and project management,” says Willcocks. “Rotating is something [Gousto founder] Timo is pretty keen on, and I’ve massively benefited from that. I’ve learned a lot in a short timeframe.”

“Your job is never very clearly defined — and there’s never anyone telling you how to do your job. It’s both wonderful, and incredibly difficult,” says Marr, who became GoCardless’ CTO once the team decided on titles. (“All three founders wanted to be CEO,” he says, which slowed down the process.) “If you’re looking to do one thing and hone that skill, it’s a pretty bad gig.”

“It’s a privilege to learn so quickly — there’s no quicker way to learn. But it’s trial by fire; we made a huge number of blunders in the early days — and the later days as well.”

“When we launched in Sweden, we didn’t realise it had a different currency,” says Honkanen. “That required a bit of work with the product team.”

Missing mentors

It’s made trickier by the fact that for many startups, there really are very few people who have been there and done this before to learn from.

“The toughest bit is that there are not many people in this industry that you can benchmark and ask,” says Honkanen, who is now head of expansion at Wolt. “[Food delivery] is a fairly fresh industry. If I want to launch in Azerbaijan, I’m learning as I go.”

“There weren’t that many mentors available,” says Marr; GoCardless was one of the earliest fintechs to get going in London. “There was this one guy I’d meet up with. We’d have three three hour counselling sessions, talking about personnel problems, internal personal crises… He was incredibly valuable. A lot of it is just managing your own psychology — you’re questioning yourself a lot.”

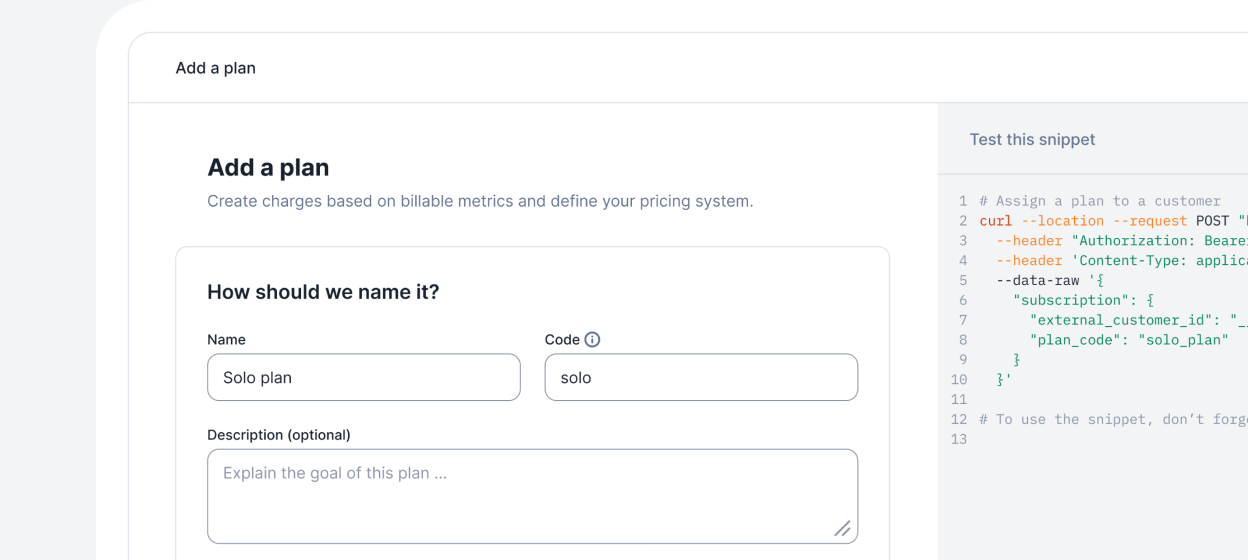

Now she’s running her own startup, Lago, Chuong wants to remedy this. “We’ve hired our first engineer, she wants to be challenged and we don’t have the skills internally — so I’m trying to find mentors to coach her, so that she keeps learning. This is what I really missed as an early employee, that I’m trying to implement now.”

“You see VCs organising things for founders, but I haven’t yet seen clubs for first employees,” she adds.

Growing up

Eventually, though, all (lucky) startups do grow up.

“One day, you’re like ‘shit, we’re 200, 300, 400 people and we’ve launched in 15 countries and we’ve raised quite a bit of money,” says Honkanen. “It hasn’t really properly hit me to this day; I’ve been living in this bubble of Wolt for five and half years.”

Some startups — and early employees — manage that transition better than others.

“You’re so proud of building a process… and then the professionals come in and are like, ‘What the hell are you doing?’” jokes Honkanen, who’s seen Wolt grow to a team of 3,000+. “It’s like somebody coming to play with your Lego.”

For some early employees, that’s the moment they choose to jump ship — as difficult as that decision can be.

“I’d worked in big companies before — and I wanted to keep learning and at some point launch my own thing,” says Chuong, who left Qonto when it was between 150 and 200 people.

“It was really hard, but I knew my learning curve would flatten at some point.”

Entrepreneurial itch

Many first employees have their own entrepreneurial itch they want to scratch.

“I wanted to see if I could do it myself,” says Marr, who launched a startup of his own in 2017, Dependabot, which he later sold to GitHub. “I’d been at GoCardless for six years and had one job before that. GoCardless was my entire career.”

Starting their own thing is also a way for early employees to redefine themselves.

“[GoCardless] was a huge part of my life — the vast majority of my friends were people at GoCardless, we were working 12 hour days… So much of your identity gets wrapped up in it when you’re doing it for so long,” adds Marr.

They also know plenty of mistakes to avoid.

“I’ve learned when stuff starts to fall apart,” says Hertmann, who is now running her own 11-person sustainable investing platform Grünfin. “I can already see the spots when the organisation changes, when you need to properly onboard people, make more of an effort to keep the culture alive.”

Worth a shot?

For anyone who is starting their own thing, Chuong has this advice: “Spend a lot of time explaining why you do things and asking them what they would do. If 20% of your good ideas don’t come from your first 10 hires, that means you didn’t hire well.”

“Give people ownership of things when they may be perceived as too junior,” adds Willcocks.

For anyone considering joining an early-stage startup, Chuong says it’s useful to think hard about what you’ll get out of it. “What’s the worst case scenario? And what are you going to get out of the experience, for yourself and your career?”

“You’ve got to think in years and not months,” adds Willcocks. “If you’re joining really early, it’s going to take a long time to get to what you might deem a success — so sign up to be in for the long haul.”

And make sure you like the founders. “You’re betting on the people more than anything,” says Marr. “The people matter a huge amount.”

“Trust your intuition. Join for the right reason. Be ready to work your ass off,” says Honkanen. “Don’t join anything for money. If you want to join for money, go work for a bank.”

Focus on building, not billing

Whether you choose premium or host the open-source version, you'll never worry about billing again.

Lago Premium

The optimal solution for teams with control and flexibility.

Lago Open Source

The optimal solution for small projects.